The Law on Handling Administrative Violations (XLVPHC), ratified by the XIII National Assembly on June 20, 2012, and effective from July 1, 2013, is an important legal foundation contributing to ensuring administrative discipline; protecting security, order, social safety, and the lawful rights and interests of citizens and organizations. From the practical work of inspection, complaint resolution, denunciation, and anti-corruption, we have identified several inadequacies in the law regarding XLVPHC. To be specific:

First, regarding the statute of limitations for imposing administrative sanctions (XPVPHC)

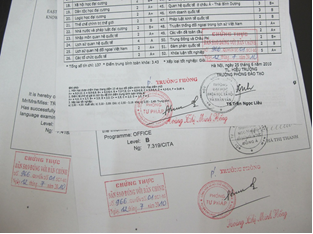

According to Clause 1, Article 6 of the 2012 Law on Handling of Administrative Violations, the statute of limitations for XPVPHC is one year; for certain specific fields, this period is two years. If the violation involves tax evasion, tax fraud, late payment of taxes, or underreporting tax obligations, then the statute of limitations for XPVPHC is determined by tax law.

Practical experience in inspection activities has revealed many difficulties due to inconsistent regulations on the inspection period and the statute of limitations for XPVPHC. Inspection laws permit executing inspections over specific periods (e.g., 3 or 5 years...) to identify violations of the inspected subjects. However, under the statute of limitations for XPVPHC, the offense may already be time-barred. As a result, inspection teams often detect violations that cannot be sanctioned or recommended for sanctions. Especially in the current context where the government aims to facilitate and support business development, reducing the frequency of inspections (no more than once a year, except for extraordinary inspections) can increase the likelihood that by the time of inspection, many violations have surpassed the statute of limitations for XPVPHC.

Additionally, the law does not exclude periods from counting towards the statute of limitations for XPVPHC. For instance, if an inspection agency discovers behavior with criminal signs and refers the case to the investigative agency, and after review, the investigative agency concludes there is insufficient basis for criminal prosecution and returns the case, by then, the violation may already be past the statute of limitations for XPVPHC as stipulated by the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations.

The discrepancies in the statute of limitations stipulated by the 2012 Law on Handling of Administrative Violations have caused confusion in practical inspection activities, allowing many violations that should have been sanctioned to evade penalties. Consequently, we suggest revising regulations on the statute of limitations for XPVPHC to align with inspection field requirements; consider not counting periods awaiting assessment results, investigative conclusions, etc., towards the statute of limitations for XPVPHC.

Illustrative image (source: internet)

Second, concerning the principle of XPVPHC

Clause 1, Article 3 of the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations stipulates: A single administrative violation is only fined once. Meanwhile, point b, Clause 1, Article 10 of the Law stipulates an aggravating circumstance is "repeated violations, recidivism." The principle for XPVPHC as such lacks clarity and consistency, causing confusion and obstacles in practice. For repeated administrative violations at different times, should point b, Clause 1, Article 10 be applied (considering it an aggravating circumstance), or should fines be imposed for each time the violation occurs according to Clause 1, Article 3 of the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations? Concerning this issue, our research group proposes clear and comprehensive stipulations on the principle of XPVPHC to meet practical requirements.

Third, concerning subjects subject to XPVPHC

Article 1 of Decree No. 81/2013, detailing certain provisions and measures to enact the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations, states: "In cases where officials and public employees commit violations while performing their official duties, and such violations are within the scope of their duties, they are not subject to XPVPHC according to the law on Handling of Administrative Violations but are handled under the law governing officials and public employees. State agencies that commit violations within their state management duties are not subject to sanctions according to the law on Handling of Administrative Violations but are handled under relevant legal provisions."

However, Decree No. 192/2013/ND-CP specifies that administrative penalties in the areas of state asset management and use, thrift practice, anti-waste, etc., can also apply to state agencies and individuals, such as officials, who commit violations while performing their official duties, and those violations are within their assigned duties.

Clause 4, Article 4 of Decree No. 192 stipulates: Organizations and individuals subject to XPVPHC under this Decree may not use state budget funds or funds originating from the state budget to pay fines and mitigate the consequences of their violations. If an organization is penalized, after carrying out the penalty decision, the penalized organization must identify the individuals at fault to determine legal liability, including repayment of fines and mitigation of the violation's consequence corresponding to the individual's degree of violation. Thus, Decree No. 192/2013 formally does not comply with the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations concerning subjects subject to XPVPHC.

In state management practices, the phenomenon of officials and public employees committing violations while performing their duties is prevalent; disciplinary measures under the law on officials and public employees are currently vague and inadequate, especially in cases of severe public service violations.

From practical state management in inspection, complaint resolution, denunciation, and anti-corruption combined with insights from Decree No. 192, it is necessary to explore expanding the subjects subject to XPVPHC to include officials and public employees who commit violations while performing their duties. This regulation would meet the need for establishing administrative discipline for state agencies and officials and public employees, aligning with the policy of enhancing control over the exercise of public power.

Fourth, on the method of detecting administrative violations

The 2012 Law on Handling of Administrative Violations outlines many fundamental and critical issues related to XPVPHC, such as forms of penalties, authority, procedures, etc. However, the Law does not stipulate methods for detecting administrative violations. In practice, administrative violations can be detected through various means such as inspection, audit, investigation, trial, etc., by competent state agencies.

Due to the absence of a unified provision in the Law, in practice, many organizations and individuals within and outside the state sector have different perceptions of issues like: What methods can be used to detect administrative violations as a basis for XPVPHC? Can regular inspection activities that identify violations serve as a basis for XPVPHC, or must it be through inspection activities? This confusion is widespread and leads to some state management agencies "abusing inspections." Thus, the Government of Vietnam should assign specialized inspection functions with the concept that only inspection activities are considered methods for detecting administrative violations as a basis for XPVPHC, even though the discovery of violations to serve as a basis for XPVPHC does not necessarily require inspection activities. Additionally, inspection activities with complex legal procedures, conditions, which current authorities and officials performing specialized inspection functions cannot yet meet, necessitate new regulations on the methods of detecting administrative violations to avoid inconsistent understanding and application in practice.

Fifth, on the authority of inspectors in XPVPHC

Article 46 of the Law outlines the authority of inspectors in XPVPHC—apart from inspectors, individuals tasked with executing specialized inspection duties while on duty, chief inspectors of departments, chief inspectors of ministries, or agencies equivalent to ministries, heads of specialized inspection teams at the ministry and departmental levels, heads of specialized inspection teams of agencies assigned with specialized inspection functions, the Law also lists heads of agencies assigned with specialized inspection functions as per Government regulations.

Currently, the number of agencies assigned with specialized inspection functions is not only outlined in Decree No. 07/2012/ND-CP of the Government of Vietnam regarding agencies assigned with specialized inspection and specialized inspection activities but also supplemented in other Government decrees and laws. Thus, it is necessary to review regulations in a broader scope concerning competent inspection entities in XPVPHC.

Sixth, regarding the responsibilities of heads of agencies and units in XPVPHC

Clause 3, Article 18 of the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations stipulates: Within the scope of their duties and powers, ministers, heads of governmental agencies, chairpersons of people's committees at all levels, heads of agencies, and units with XPVPHC authority are responsible for detecting errors in XPVPHC decisions they or their subordinates issue and must promptly amend, supplement, or cancel such decisions and issue new ones within their authority. However, in practice, implementing this provision is impractical as the law lacks specific guidelines on the procedures for issuing, amending, supplementing, or canceling administrative decisions. The Government Inspectorate believes this provision needs to be reviewed and adjusted to ensure consistency with legal provisions on the issuance of administrative decisions.

Seventh, regarding the confiscation of exhibits and means of administrative violations

Article 26 of the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations stipulates: The confiscation of exhibits and means of administrative violations involves appropriating into the state budget items, money, goods, and means directly related to administrative violations and is applied to severe administrative violations committed intentionally by individuals or organizations. Thus, the confiscation of exhibits and means of administrative violations only applies to severe violations committed intentionally by individuals or organizations. However, in practice, particularly in customs, commercial, and logistics sectors, individuals or organizations transporting goods often do not accurately know, nor truthfully understand, the nature of the goods they carry, making it challenging to prove intentional wrongdoing, even if the violation is severe. We propose that the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations provide more detailed guidelines on this matter.

Eighth, on the execution of administrative penalty decisions

The execution of administrative penalty decisions in cases where the sanctioned individual dies, goes missing, or the penalized organization dissolves or declares bankruptcy is stipulated in Article 75 of the Law. Article 9 of Decree No. 81/2013/ND-CP provides details: "If a penalized individual dies, goes missing, or the penalized organization dissolves or goes bankrupt under Article 75 of the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations, and the penalty decision is still within the enforcement period, the person issuing the penalty decision must issue a decision to partially execute the XPVPHC decision within 60 days from the recorded date of the penalized individual's death on the death certificate; the recorded date of the individual's disappearance on the missing person declaration; or the recorded date of the organization's dissolution or bankruptcy decision. The execution decision includes the following content: a) Suspension of imposed penalties, reason for suspension, except in cases stipulated in point b of this clause; b) The confiscation of exhibits, means of administrative violations, and continued execution of remedial measures."

Practically, many enterprises have exploited this provision; when facing large fines, they initiate dissolution procedures, later establishing new enterprises to evade penalty obligations while the government lacks effective controls. Thus, clear regulations are needed to monitor cases where enterprises undergo dissolution procedures to evade administrative fine obligations.

Additionally, other difficulties, obstacles, and inadequacies relate to the right to explain stipulated in Article 61 of the 2012 Law on Handling of Administrative Violations; the timeframe for handling confiscated exhibits and means of administrative violations; and guidance documents for implementing the Law.

We believe it is essential to study and supplement the right to provide explanations for involved parties when subject to "the confiscation of exhibits and means of administrative violations worth 15 million VND or more for individuals, or 30 million VND or more for organizations"; add provisions to Clause 3, Article 82 of the Law allowing extensions in complex cases, up to a maximum of 30 days. These adjustments aim to address practical issues in handling certain types of exhibits and means that need to be auctioned according to point d, Clause 1, Article 82.

The above are some difficulties and obstacles in implementing the Law on Handling of Administrative Violations identified through inspection works that require compilation and consideration by competent authorities to offer guidance and address them, aiming to perfect the law on Handling of Administrative Violations to meet current state management needs.

Source: Nguyen Thi Bich Huong, Legal Department - Government Inspection of Vietnam

Article table of contents

Article table of contents